Starr-Gennett History

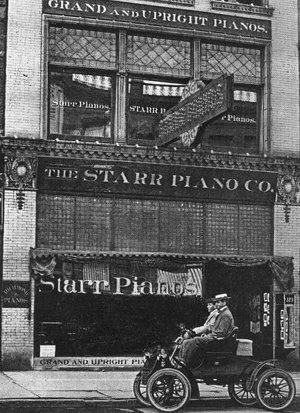

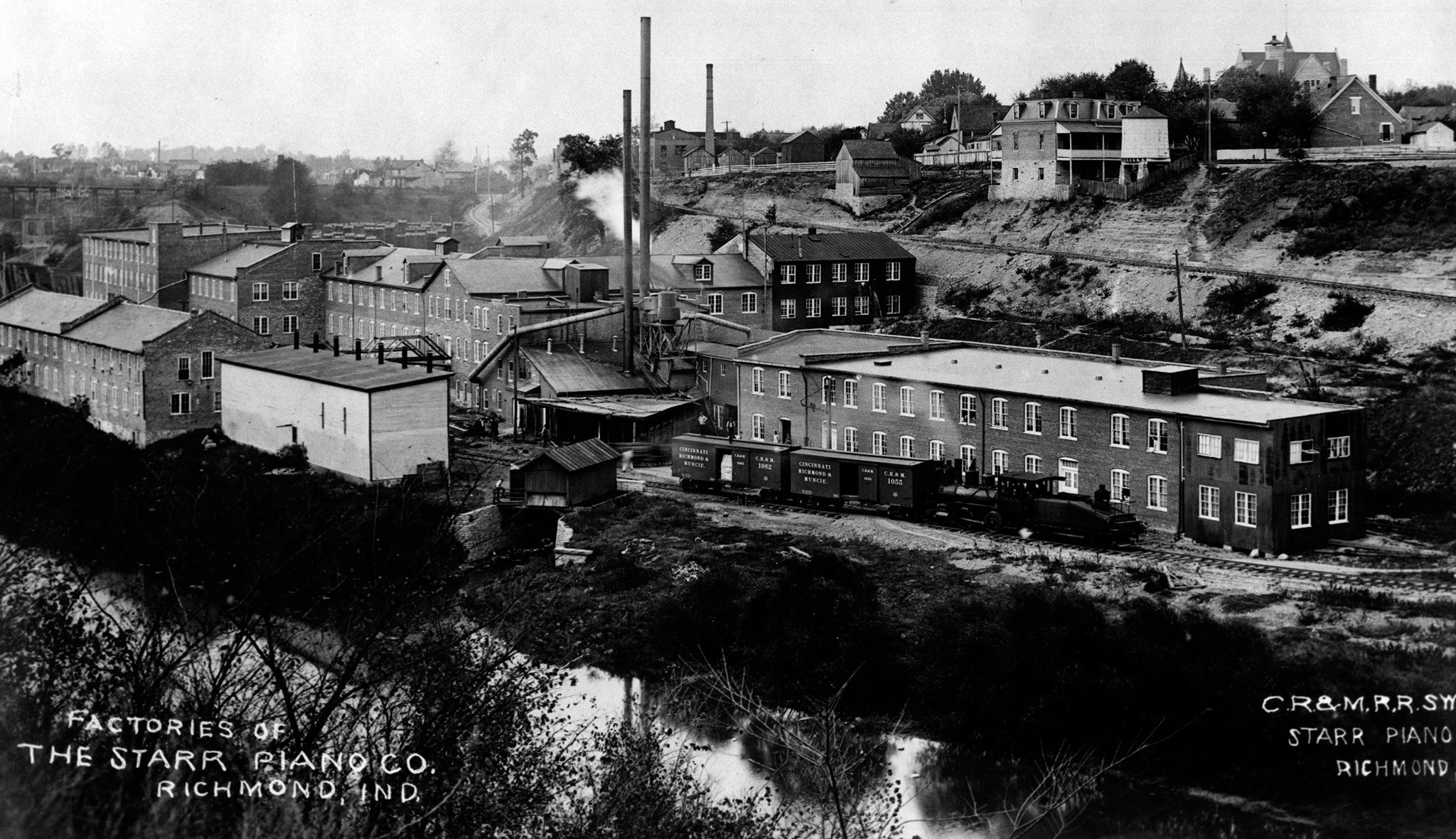

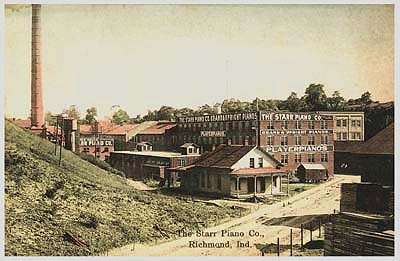

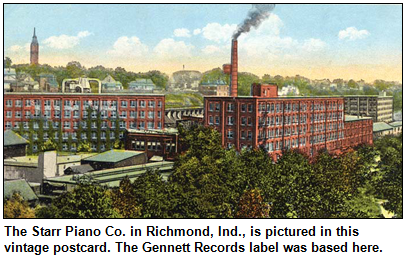

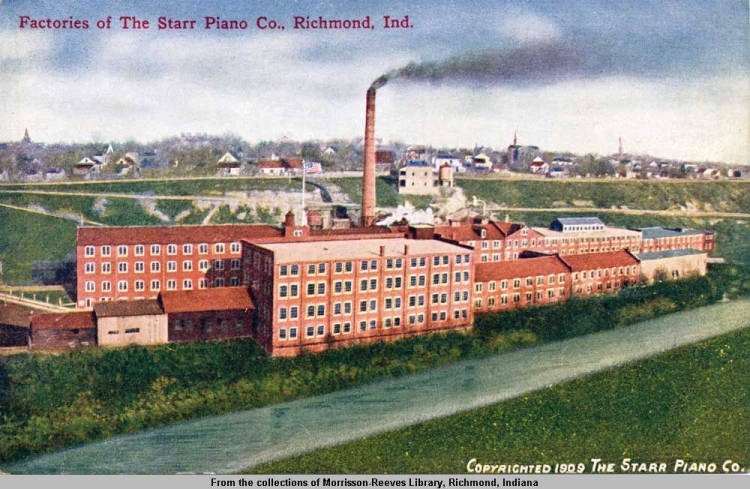

The Starr Piano Company story begins in Richmond in 1872 when two business leaders, including James Starr, partnered with Alsatian piano craftsman George Trayser to open a small piano factory downtown. By the mid-1880s, the growing factory operated in the gorge of the Whitewater River under the “Starr” name. In 1893, three Southern investors, including Henry Gennett of Nashville, Tennessee, acquired control of the company. At the turn of the century, the Gennett family assumed full ownership of Starr Piano.

By then, the Starr factory in the gorge of the Whitewater River had become one of the largest in the world devoted to the production of pianos. That it made room for quality as well as quantity is evident in the top honors the company’s top models took at national and international expositions.

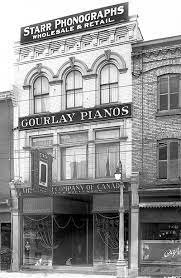

But even before the United States entered World War I in 1917, the phonograph had begun to displace the parlor piano as the primary “home entertainment center.” When key phonograph technology patents expired in 1916, Starr took advantage of its mechanical and woodworking facilities to add phonographs and phonograph records to its product line.

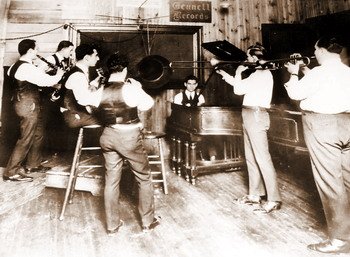

At first, all or most recordings were made in talent-rich New York City, sent to Richmond for duplication, and distributed from there with a Starr label. But because other piano and phonograph companies were reluctant to sell in their own stores records bearing the name of a competitor, Starr soon changed its label to Gennett, for Henry Gennett, by then the company’s president. Thereafter, Starr’s recording business operated as Gennett Records.

Starr’s willingness to record musicians not yet in the musical mainstream, along with its hands-off attitude toward their work in the studio, has led at least one record industry scholar to call Gennett Records the prototype of the independent record label.

Two imperatives seem to have driven marketing for Starr and Gennett. First, Starr’s management knew that to keep selling pianos, they had to help assure a continuing supply of trained pianists and new sheet music for them to play. Trade journals of the period reveal that Starr marketed its pianos to schools and sold other aids to keyboard instruction in the classroom. Moreover, the company sold sheet music in its many stores worldwide and may even have become the silent partner of a music publisher in Chicago.

Starr and many of its competitors also built automatic, or “player,” pianos that could be operated by anyone and used pre-recorded piano “rolls.” Although that advancement in piano technology may have moderated the push for keyboard training and the publication of sheet music, it created a need for piano rolls, which Starr filled by having local pianists record them for reproduction on equipment the company bought from a failed roll maker.

The piano roll, though it still persists, quickly lost much of its market to the phonograph record, which could capture the sounds not only of a piano, but also of every other kind of musical instrument including the human voice. Exceedingly complex pianos and organs had been produced that could mimic an ensemble— imperfectly—but they were too expensive to purchase and maintain for home use, and were usually found in commercial establishments where they were coin-operated and served much as record-playing juke boxes did later.

Starr’s decision to enter the recording business probably followed the marketing logic that led the company to encourage piano instruction and produce piano rolls: If you wish to sell phonographs, make sure buyers have records to play on them. Unfortunately, Starr encountered a major obstacle in the form of a recording process patent that the “big three” in recording, Columbia, Edison, and Victor, relied on to block other companies trying to enter the field. Starr also found that the big three tightly controlled East Coast music talent by paying much more for it than start-ups like Starr could afford.

Starr’s great and everlasting fame rests on taking leadership among small record companies in overcoming the technical and talent constraints they all faced, and in opening the way for every independent record label that followed. Starr successfully challenged the recording process patent in a five-year legal battle that went all the way to the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. And to find affordable talent, Starr pioneered in recording various kinds of regional music, then little known in the nation at large, that would eventually engender nearly all the popular music styles heard today.

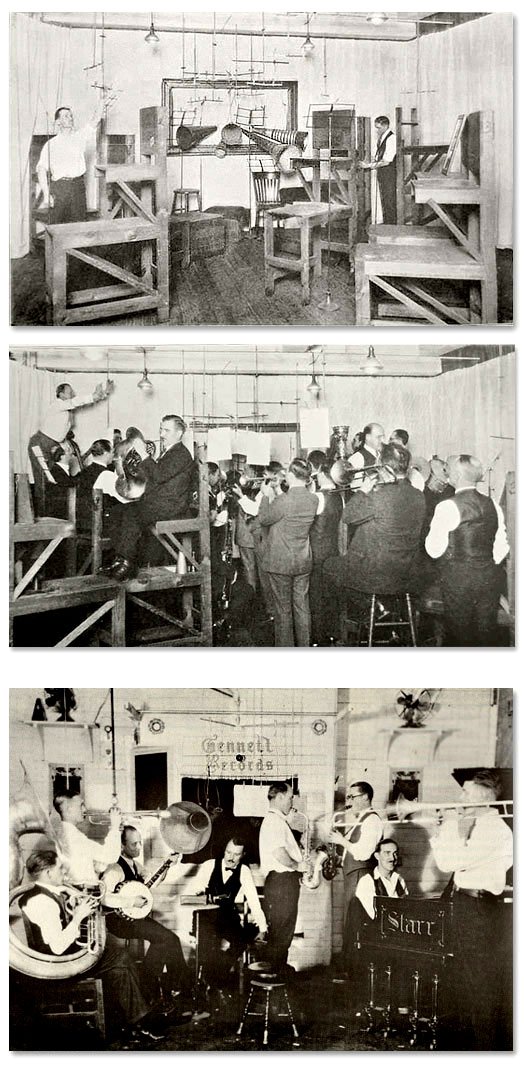

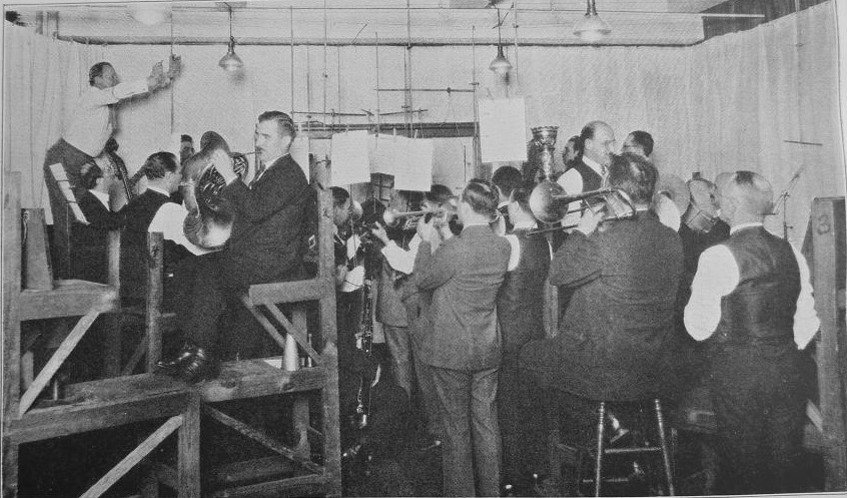

Starr strengthened its talent search by setting up more Gennett recording studios where needed, including a permanent one in Richmond, to give regional musicians easier access. Some of Starr’s store managers in key regions also functioned as talent scouts.

The company improved its standing with musicians by allowing them artistic control of their recording sessions. Management simply asked for three “takes” of each recording from which to select the one to be reproduced and sold. Most other companies employed “A&R men” (artist and repertoire) who essentially told the musicians what to play, how to play it, and sometimes with whom to play it. Actually, the sheer volume and diversity of music produced by the tiny Gennett recording staff probably left them little time for meddling with the musicians.

Starr pioneered in recording various kinds of regional music, then little known in the nation at large, that would eventually engender nearly all the popular music styles enjoyed today.

Starr’s willingness to record musicians not yet in the musical mainstream, along with its hands-off attitude toward their work in the studio, has led at least one record industry scholar to call Gennett Records the prototype of the independent record label. That distinction is especially significant because “indies” are held in high regard as principal agents of musical change.

The second marketing imperative for Starr and Gennett was to cultivate broad audiences for relatively obscure but affordable talents playing the equally obscure music now known in part as jazz, blues, country, and gospel. The company’s worldwide network of piano stores undoubtedly facilitated distribution of its phonographs and records, thus helping the music catch on.

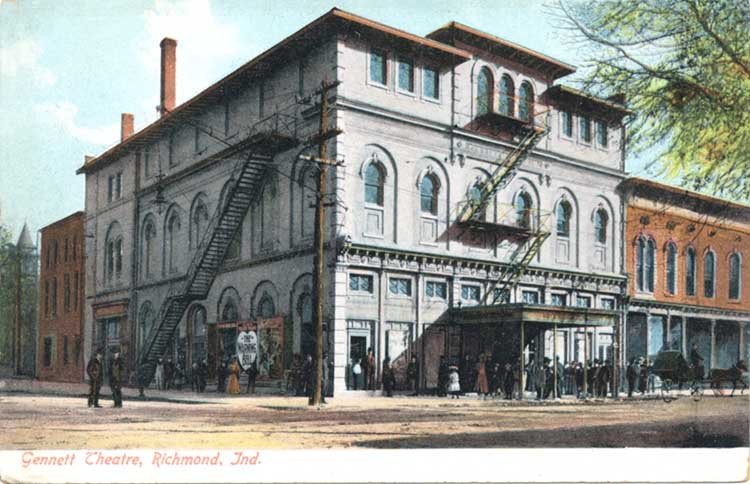

Jazz enthusiasts have long considered Richmond and Gennett Records “the cradle of recorded jazz.” Through Gennett, Starr also nurtured other forms of popular music, ethnic music, sound effects for radio and film, and even preservation of the spoken word.

Sadly, the market crash of 1929 and the ensuing Great Depression put all but the cheapest records beyond the reach of many people, causing Gennett to maintain only its economy label, Champion, after 1930 and to abolish even that one by 1934. Its line of sound effect records was maintained for a few years longer. Decca Records and Mercury Records leased Starr’s record reproducing facility at various times, and several short-lived attempts were made by other outsiders to revive the Gennett label.

Although Starr still manufactured pianos, sales continued to decline. To compensate, the company diversified again, but this time away from music. It used its mechanical facilities to produce refrigeration equipment. That sideline made sense despite the hard times. City-dwellers, who had home electrical service by then, were rapidly replacing their old-fashioned ice boxes with refrigerators.

Ownership of Starr and Gennett had long since passed to Henry Gennett’s four offspring and their heirs. Some decided to liquidate their holdings and pursue other ventures. One branch of the family headed to California to manage the company’s Pacific Division and build on Starr’s refrigeration experience. The venture flourished and was eventually renamed Refrigeration Supplies Distributor, which is still owned and run by Gennett descendants. The heirs electing to carry on in Richmond kept Starr Piano afloat until 1952, when they sold the entire plant to distant investors whose redevelopment plans never materialized.

By 1990, all but one of the vacant factory buildings had been razed. The survivor was stabilized recently, re-purposed, and renamed. Now called the “Starr-Gennett Pavilion,” it lives again as the all-purpose activity center in Richmond’s Whitewater Gorge Park, which incorporates the site of the former Starr complex.